upper:

lower:

current:

show:

doc-height:

progress:

safari:

DEBUG: EMPTY

"You Get What You Get, and You Don't Get Upset"

THE HOLLYWOOD TALENT AGENT

Reading about Hollywood actresses coming forward with their #MeToo stories in 2017, many times I found myself thinking: “Why has it taken them this long to talk publicly about the abuse they went through? Why have they been silent for all these years?”

One answer lay on the surface. Obviously, they had to gain enough security, privilege, and recognition to let their stories of trauma be seen. As young actresses being sexually harassed, no one would have treated their experiences with respect. Instead, the system that enabled their abuse – Hollywood’s patriarchy, classism, and corruption – would have effectively banned them from the profession. At that moment, their voices wouldn’t have been widely heard and supported. Their talent wouldn’t have been evidenced by careers spanning for decades. Their truth wouldn’t have brought about as much accountability and meaningful change as it has these days.

But there was also a more important, deeper reason. I came to understand it after myself going through essentially the same abuse at the hands of the Hollywood’s powerful.

The reason is, after going through a traumatic experience like sexual harassment and abuse of power, you need time – sometimes years or even decades – to filter out emotional intensity, gain perspective, contextualize, and distill lessons from the experience in such a way that, when the story gets shared, it can bring about empowerment, empathy, and systemic accountability, rather than vengeance, defamation, and blaming.

In 2018-2019 I went through one of the most devastating experiences of emotional abuse in my entire life. Previous episodes in this series pale in comparison to what that person, being a powerful man from Hollywood, did to my life. It’s a story of how, over one year, his lust, narcissism, greed, and cowardice destroyed my self-worth, my sense of legitimacy as an artist, and even my sanity.

By and large, this is my #MeToo story.

However, I only write about it now, one year after this relationship ended. I understood the abuse and its particulars a long time ago. As someone equipped with mental health knowledge from my previous research, in the back of my mind I didn’t fail to identify toxic patterns and red flags in his behavior. I realized that what kept me trapped in that relationship was his privilege and my disadvantage.

I knew how to write. I had an Instagram page and a community. I had people check in with me and wonder why I stopped putting out new content. It looked like I had skills and space and relationships to share what was going on.

Why have I been silent so long, still?

First, it was about my fear. Old programming dies hard. As a man I was raised to believe that I have no business sharing how I feel. That whatever emotionally significant experience I go through, the “right thing” to do is to just suck it up and soldier on. Because, as the culture told me, “real men” don’t do vulnerability. They don’t own, explore, and talk about their emotions because it’s weakness. It’s taken me years and two episodes of terminal clinical depression to unlearn that bullshit and reinvent the concept of a “real man” in a way more aligned with reality – based on courage, integrity, and self-worth, rather than fear, armor, and scarcity. However, I still struggle with it. No matter how much I evangelize around vulnerability, I’m not good at opening up, especially about experiences where I got abused or taken advantage of – I’m scared of being seen as weak.

But that fear, like any kind of bullshit, could be easily reality-checked with time. In my experience, fear gets invariably outweighed by the critical understanding of empathy and empowerment I can create by sharing my lived experience, especially when it clearly reflects forms of systemic oppression.

Then the question becomes: how do I share my story? How do I tell it to maximize its positive impact – empathy, critical awareness, and call to courage and accountability? How do I tell it in the rawest and most honest way possible, owning my part in what happened? Putting aside my unfiltered emotions and unrelatable circumstances, how do I extract relatable, widely applicable, most powerful lessons from my experience to share and thus create added value, rather than just get attention and publicity?

Now, this is what’s taken me more than one year, as I was working on my upcoming YouTube channel. Recalling. Writing down. Analyzing. Reality-checking. Getting in touch with screenshots of chats and other pieces of evidence, painful as it was. Connecting the dots. Contextualizing. Distilling. And today, the truth finally demands to be told.

Have you ever met a gay man rationalizing homophobic violence? A gay man saying that thousands of American LGBT teenagers get kicked out of their homes by their own families "for their spiritual enlightenment"?

Have you ever had a friend telling you that dying from cancer in your thirties — not because your cancer is untreatable, but because you don't have access to adequate healthcare — is a destiny-sent gift?

Well, today you're in for a treat. Meet José, a talent agent from Hollywood.

BEGINNING

Unlike in previous episodes, here I will call the person by name, although José is not his real name.

I met him on Instagram in the beginning of 2018, following his comment on the post of a person that we both followed. As the experiences with the hijabi poet, the vegan make-up artist, and other people came to their toxic closures, I didn’t stop looking for new people to connect to around my work. No matter how easy it was to question my personal worth as a result of those abusive experiences, the worth of my artistic work was measurable and observable, and the evidence from my recent research on empathy, privilege, and intersectionality reinforced my trust in the relevance of the story my book had to tell, and the impact it could make if shared on appropriate platforms.

So yes, now even more than two years before, I knew I had to find allies having the privilege I lacked. Like-hearted folks standing for social justice in real, no-BS ways. Folks willing to do the work. Folks putting truth and courage over comfort. Folks understanding and practicing real spirituality. Folks recognizing the lack of meaningful human connection in our culture and recognizing the power of art in building that connection. I did believe that such people existed – because I existed. And the fact that I didn’t have enough privilege to get this work off the ground on my own was a result of randomness. I did believe there would be someone willing to recognize the value of this work and share their privilege with me – because this is what real fight for social justice looks like.

So now, I saw the profile of another upper-middle-class American man, living in Los Angeles, having around 40k followers, working as a talent representative at his own agency. Remarkably, his pictures didn’t look narcissistic or shallow to me right off the bat. He posted quite a lot about personal development and spirituality – enough for me to allow the possibility that we had common ground in values. In retrospect, I see one factor that, without my conscious awareness, positively influenced my perception of him: he had a Hispanic name. Just like in the case with the Christian fashion stylist, the fact that he was a Latino, originally from Venezuela, made me believe he would be likely to connect to and understand my life experience.

This assumption reflected a pattern that these days I work hard to eradicate. Somehow, in the process of developing my social justice vision, I bought into this misleading concept of group identity. It means that if I share certain identity with someone, like the identity of race, ethnicity, class, orientation, religion, etc. then this person thinks like I think, feels like I feel, lives like I live, and sees the world the same way I see it. This is the bullshit idea claiming that our identity, whether privileged or oppressed, defines our values, our perspective, and our way of walking through life more than our individual choices. For me particularly, it played out in believing that people “like me” are more trustworthy than people “different from me” on the surface. That Hispanics, for example, are more trustworthy than Anglos. That Christians are more trustworthy than agnostics. That people originally coming from socioeconomic disadvantage and third-world countries are more trustworthy than people who grew up middle-class in the West.

Over the years and through many relationships, life has given me enough evidence to reality-check that notion. It’s horseshit. No, Hispanics aren’t any more or any less trustworthy than Anglos just because they’re Hispanics. And no, Christians don’t possess any higher or lower level of integrity or moral standards compared to agnostics just because their Christians. No, just because someone grew up in a third-world country and/or amidst socioeconomic oppression doesn’t mean they will be interested in fighting for social justice like I am. Because how I conceptualize my Hispanic identity, my Christianity, or my trauma of growing amidst poverty can be very different from how other people conceptualize and operationalize those things.

However, at the beginning of that relationship in 2018, I still held on to the belief that Hispanics are “my people”. Aside from that, my sense of self-worth and critical awareness were heavily damaged by previous abusive experiences. Traumatic pressures were increasing in my life in Russia, with no time and space to contextualize what happened, to rise strong, and to distill lessons to be learned for my future relationships.

Back then, I didn’t even follow him. I thought I’d come back to research and read his feed later. I just left a casual comment on one picture that really surprised me: him skiing on a snow-covered slope, amidst the rest of the photos showing the sunny climate of California. I read the geotag on the photo, and just said it was interesting to learn that there were ski resorts in that state.

A few hours later, he started following me. Moreover, he even DMed me, “Hi Jorgito! Why haven’t you followed me yet? ;-)”

My critical awareness went offline. I was just shocked by the fact that this privileged dude from Los Angeles followed me after my goofy, casual comment. It didn’t even occur to me that he could be gay and just liked my pictures. With my sense of self-worth still reeling from my previous experiences, I took his behavior as a bid for meaningful connection.

So I started following him immediately and replied in the chat. We texted back and forth a bit before I went to sleep, and the next day I took a closer look at his page. Yes, he appeared to be quite an intellectual person, interested in spirituality and psychology. He’d also recently started doing stand-up comedy, and his performances were really great. At the moment, I didn’t realize he could have some connections to help me with my work. Honestly, I didn’t actually understand what a talent representative was. I saw his photos with one or two celebrities, but there was no evidence he had access to those particular people I was interested to connect with. Anyway, I just liked him as a person.

I started liking him even more a couple weeks later, when he started hosting a podcast centered around innovation, personal growth, and spirituality. He had entrepreneurs and creatives share their stories of success, and from the very first episode featuring a trans-rights activist, there was a lot of stuff that resonated with me.

So we started discussing it. Over email and in texts. He always responded respectfully and behaved like he appreciated my feedback. From those early stages of our correspondence, he started complimenting my intelligence. It was gradual but consistent. After a month he told me that my train of thoughts “was brilliant” and wondered why I didn’t start my own podcast.

Well, he didn’t know I’d written a book already. Our conversation hadn’t so far provided the context for me telling about it. But I decided I would tell him at one point. Given my multiple experiences from 2016, I still had this fear that people would ghost me as soon as they learned I had a book I was trying to get off the ground. So the story about my book and its role in my life was too vulnerable to be shared in a casual chat. However, the fact that he liked my feedback on his podcast topics created the expectation that he’d be interested to learn about my artistic work, which revolved, essentially, around the same values. It was a normal expectation. Except I didn’t know I was again dealing with one of those people who consistently communicate signals to inform expectations and encourage emotional investment on your part, only to crush you down later.

He made me feel like we were gradually growing a friendship. Once in April, when he shared about his Mom being a cancer survivor, I took it as an act of vulnerability. Trust, as I knew from research, is created in such small moments of courage, which, after all, aren’t that small given the deficit of courage in our culture. So I thanked him for sharing this and then recorded a voice message where I opened up about my recently diagnosed tumor and the fact I didn’t have access to necessary treatment in Russia.

It was the first voice message I ever sent him. Prior to that point, we had only communicated through texts. He saw that message. But he said nothing in reply.

That was the first red flag in this story that I missed – the moment I got really vulnerable, I got rejected and ignored.

In fact, I didn’t have enough time and space to think about this at the moment – my focus was on the relationship with the Christian fashion stylist, which, after having started in February with big promises, big commitments, and big value statements, was now going downhill after she learned about my place of residence, my socioeconomic status, and my health situation. I still didn’t recognize that it was her true colors coming out. I still made good assumptions about her and thought I could do something to fix that relationship.

So I even reached for José’s help. I realized that doing negotiations with celebrities for work, he could have some skills necessary to effectively talk to people of these social circles – the skills I believed I lacked. I told him I had an unexpected setback in a hugely important professional relationship – the kind of chance coming once in a lifetime (I really believed so at the moment). I asked him if we could have a FaceTime about it on the weekend – so he could offer some advice from his experience.

He agreed, and honestly, I wasn’t surprised he did. Given his treatment over the months, I’d already taken him as a long-distance friend. In his emails and texts, he’d told me he was rooting for me. Now, seeing his normal reaction to my bid for connection, I even started rationalizing the fact he hadn’t responded to my voice message about the tumor. Maybe, I thought, he was shocked and just didn’t find anything to say. Or maybe, someone or something interrupted him as he was listening.

So we arranged to have that FaceTime on the weekend. On Friday night, which was Friday morning LA time, I texted him about the day and the time we’d see each other. Eleven hours of time difference were no joke. It all had to be planned and set up in advance. I asked him about his available time slots.

Waking up the next morning, I saw there was no reply from him, although he’d seen my message. From his Instagram Stories, it was obvious he wasn’t having any emergency going on. Just an ordinary day of his fortunate, upper-middle-class American life. Meaning that he’d just decided to ignore me.

THE HEDONIST

I’d been there enough times previously. I’d had enough people chicken out of communication as soon as the conversation got real. So at that point, I decided I’d never text him again. I’d already offered enough vulnerability to now offer even more to someone who obviously wasn’t interested to see it.

During the weekend where our first videochat was supposed to happen, there was no word from him. In his Stories, there were a workout and a party. He was just having fun, even though I’d told him I needed his presence and support.

I should have believed his true colors when he showed them to me. Right at that point. I should have unfollowed, and probably even blocked him. But some part of me – in retrospect I see it as a seed of doubt about my own sanity, artfully sown by an abuser – this part told me to just not text him anymore, but not cut him off completely. Also, in the back of my mind, I saw his possible help as my plan B with the work – it was getting clear that he might have necessary contacts.

About a month later, when the situation with the Christian fashion stylist was over, I woke up to an Instagram notification about his new post. It was the screenshot of an article interviewing him about his career in a fashion magazine called The Hedonist. So I left him a comment about the meaning of the word hedonist – a complacent, selfish person, celebrating their privilege and showing no concern about the pain of their fellow human beings. I reminded him of his friendship statements made over the months and the fact that, when the time came to practice them, he chose to have fun with his privileged friends instead of having a FaceTime to support me in my critical situation.

I thought he’d just delete my comment and block me. In my experience, that’s what people always did when confronted about their hypocrisy.

But guess what? Instead, he wrote me a long DM, acknowledging his mistake and apologizing. He said that on that weekend “he knew he wouldn’t have available time for me”. He said he was missing our chats and my feedback on his podcast episodes. He said he hadn’t even known the meaning of the word hedonist, and that in fact he cared about what was going on with me. He offered to have a FaceTime on the weekend to come and said he’d love to see me live.

Again, he artfully sent my critical awareness offline. I didn’t ask him obvious questions. If he realized he didn’t have available time (which can happen), why didn’t he just let me know? If he missed our chats, when didn’t he text me first? Instead of asking these legit questions, I just silenced myself and “assumed good” about him. No, it wasn’t real generosity. I was just too broken, too hopeless, and too desperate after the crushing betrayal of the Christian fashion stylist, and now I saw him as someone else who could help with my work.

Above all, he apologized. This behavior gaslighted me the most. Because previously in my life, for all the abundance of emotionally abusive people, I’d never seen any of them apologize in a way that showed the understanding of their mistake. Abusive people, as I believed, only deny, blame, and rationalize. Most recently, that’s what the hijabi poet did. That’s what the Christian fashion stylist did.

And this dude, he behaved like a normal person would behave after making a mistake. So, subconsciously believing that I would hardly find anyone else to connect to around my work in the near future, I came back to building a friendship with him.

That’s where the real, hardcore cycle of abuse started, following the same classical phases it follows in romantic relationships – idealization (a.k.a. love-bombing), devaluation, and discarding.

MAY

So a few days later in May, we actually did a FaceTime. He didn’t ignore me. He showed up on time. He appeared warm and raw and down-to-earth from the beginning – literally from the time he said Hi. We saw each other live for the first time, but it felt like we were on the same frequency – like we were friends knowing each other for ages.

Now, I remember I had the same feeling during my first WhatsApp conversation with the Christian fashion stylist. She talked to me as a good old friend. And with experience, I’ve come to see it as a telltale sign of abusers – no, even if you’re as straightforward and wholehearted and raw as it gets, you don’t get this warm with people the first time you see them. It’s easy to fall for this “friendly treatment” when you were bullied or humiliated or betrayed before (my case), but it’s just not normal.

There was something else that wasn’t normal. Ten minutes into the conversation, he asked me: “So are you dating someone?”

I was stupefied. Why would he ask me that?

“No,” I said, “I’m single.”

And before I had the chance to tell him that dating anyone was not in the cards for me at the moment – that I was working my ass off to get out of Russia and start over in the West, laying the foundation for my creative career – before I opened my mouth to say this, he replied:

“Wow, how come? You’re so handsome. If you were here next to me, me and you would do some dirty things that my dog would be embarrassed to see.”

Then he laughed. I was speechless for a moment. Okay, it became clear that he was gay. And that wasn’t a problem. The problem was that he assumed that I was gay before taking the trouble to ask me about my orientation. Just because he liked me. Or just because he saw LGBT-related posts on my feed – and assumed I had a skin in the game.

Instead of setting boundaries, I laughed it off. Remember, I was already hooked emotionally. Just like a young actress being harassed by a Hollywood producer, I knew this person in front of me had power and privilege. Based on my previous life experience shaped by disadvantage, I felt like my talent and my work would stay unused and unclaimed forever, eating me up from inside, unless that person used his power and privilege to help me, opening the gates of this industry where I’d dreamed to work since I remembered myself.

It was also easy to dismiss this minor episode of sexual harassment because he was very talkative and quickly steered the conversation away. In fact, we were on the same frequency and both talked a lot and I didn’t notice how one and a half hours passed. Although his sexual advances made me feel uncomfortable in the beginning, I actually enjoyed the rest of the conversation. He appeared smart and funny and self-aware. And, it looked like me and him shared big interest in many important topics related to spirituality and personal development. So we arranged to have videotalks regularly.

At that point I sincerely believed we’d be growing our friendship this way.

IDEALIZATION

SUMMER

During the next two months, he made it clear that we actually had a friendship. Yes, this wasn’t something I made up just because I needed his help.

Instead, it looked like a normal, gradual, reciprocal growth of trust and vulnerability. We FaceTimed almost every weekend, and he never failed to show up. We got carried away in our fluent conversations, and I didn’t notice how time passed. Because of the time difference of eleven hours, the only available time slot was night Moscow time/ morning LA time, and he always apologized for having to end the conversation and go on with his day. He made me feel like he enjoyed how we hung out.

Then, clear, unambiguous, literal statements of friendship followed – on his part, not mine. I never was the first to call him a friend. Instead, he told me how much he “appreciated our friendship”, how grateful he was that he met me, and how great it would be if we could meet one day in real life. I bullshit you not, he said those things. Thanks to technology, I have proof of that in my messenger apps and my mailbox.

This impression of him being a wholehearted, raw, and warm person was reinforced by what I saw other people say about him. One of his LA friends, who regularly commented on his posts, had his birthday picture on her page where she mentioned what an extraordinarily kind person he was. She said he was someone who always showed up during hard times, someone she could trust and rely upon, in one word – her “ride and die”. Doesn’t this say enough about his loyalty and integrity? Well, there was another friend of his who, while being interviewed on his podcast, mentioned how a few years ago she had an idea of a movie or a book (I don’t remember exactly), and when she told him, he put her in contact with people who made this project possible. And he replied he was happy to do that. This piece of their conversation blew up my mind – because that was the exact kind of help I needed with my work. And, as it sounded, he saw nothing wrong about providing that help through his connections. Finally, on his Instagram page, there was a picture of him with an internationally famous Venezuelan fashion model who was now one his best friends – and the story of how, almost two decades ago, meeting her at some event and telling her about his work brought his career to the next level. All that information communicated clearly: he was someone who understood the importance of personal connections in the artistic world. He was someone who received help and gave help graciously, honoring our shared humanity.

Aside from that, it finally occurred to me that he was a professional in the exact field where I needed help – the field of representing artistic talent and negotiating with big companies and big figures in the industry. Yes, unlike all those people I’d met before, he did it professionally. He’d been doing this for a living for about 20 years now, and he was obviously successful. He had the skills and connections to represent work like mine.

Following these findings, next time we FaceTimed I brought this topic up. No, I still didn’t feel we had built enough trust to tell that I needed help with my work. But I had to find out how he saw giving and receiving help in his professional area – to understand if my impression about him was right.

He said he was happy to help his friends with their innovative and creative projects whenever he could – and he’d been himself given a lot of help in the past. He added, “LA is a small town. When you live here for 15 years, you know almost everybody. And everybody who has a phone is potentially a producer.”

I thought to myself, “What a great guy he is. He rubs shoulders with the powerful and the influential, and he makes it look like it’s no big deal.”

See guys, just like him I also had a phone. But I couldn’t be my own producer or my own talent agent because I didn’t have the contacts of those who would be interested in my work. And he made it clear to me that he had the contacts. That he had the access. That he could make or break dreams of someone as underprivileged as I was.

At the moment, I didn’t recognize that, instead of communicating his good will to help others, he was simply waving his privilege in my face. Instead, I thought he meant what he said. Let’s see reality for what it is: he’d been calling me a friend, making me feel seen and welcome and appreciated, and now he confirmed he’s happy helping his friends through his connections.

Based on his statement, it was logical for me to assume: José’s gonna be willing to help me too. Especially given that my project is innovative, and he appreciates people thinking outside of the box. Especially given that my book addresses homophobia, and he’s gay. Why wouldn’t he be willing to help me? At least, why not try?

Still, I didn’t feel ready to ask for his help immediately, after these values have professed. Given the scars from my previous relationships, it was too much vulnerability, and I didn’t feel there was enough trust between us.

And then, as if wanting to increase that trust, he got vulnerable in front of me on a new level.

SURGERY

He told me he was going to get a cosmetic surgery. He’d been thinking about it for quite a long time, but he hadn’t made up his mind until recently. Because he knew he’d receive judgment and trivialization around this issue from most people in his social circles. Like, he would be shamed for spending a lot of money on the surgery, instead of sending money to his parents. He would be shamed by his friends because having cosmetic surgeries was seen as emasculating. (Yes, to my great surprise, these patriarchal stereotypes existed even in Hollywood’s gay community – where people putting piles of money into cosmetic procedures and surgeries still had to pretend their good looks were “natural” – isn’t this what Brené Brown calls a shame-prone culture?).

I thanked him for sharing this with me. He was forty years old now. From my research on the intersection of gender and sexuality, I’d known that body shame, and aging as a related aspect, were powerful forces in gay men, blowing appearance imperfections completely out of proportion. It was all the more powerful if you lived in a place like West Hollywood: where your worth was mostly defined by how you looked, where regardless of their gender, people went to all lengths in their anti-aging efforts, where comparison and fitting in were running the show.

Yes, it was hard to live under these pressures. Especially if you’re a gay man, going into middle-age, and still single.

I’d never been in his shoes. However, I’d had a similar emotional experience in the past. In the beginning of 2014, during the remission after my first depression attack, still being a poor person from a third-world country, I’d also had a cosmetic surgery. I’d gotten a microinvasive hair transplant in Spain. Working at my semi-slavery job in Russian healthcare, I spent almost all the money I’d amassed over one year on this surgery. I’d also got shamed and judged and ridiculed – by my family and by the people I socialized with. But I went for it, because deep down in my heart, I knew why it was important – I dreamed about making a career in performing arts after finishing my book and moving away from Russia. For a performance artist, looks are damn important, whether we like it or not. We may spend hours condemning the pop culture for its shallowness, but it doesn’t change the fact: if you’re going bald in your thirties, you won’t fit the image most producers want. You won’t get record deals and you won’t be seen as relevant by the audience as another handsome guy with thick hair. So yes, I had to make this huge, devastating investment for my future. The future that I sincerely believed was there to come.

Now, four years later, my situation was completely different. I no longer had a job that even covered my inevitable expenses like food and gas. My current job at best yielded $100-$150 a month. I’d been borrowing from the scarce savings I’d made over the years that had shrunk twofold in 2014 as a result of Russian ruble devaluation, and these savings were coming to an end. I’d been diagnosed with a skin tumor that was most probably malignant, and now, with no access to adequate healthcare in Russia, I didn’t even have two thousand euros to go to Spain and have that tumor removed. Every day, I was waking up thinking if my tumor had already gone metastatic. Instead of moving away from Russia, publishing my book and starting a career in performing arts, in fact I got trapped in a yet bigger trauma and misery than I’d been in 2013, when I started to write the book.

So now, what would I respond to an upper-middle-class American gay man in Hollywood, having celebrities among his friends, who was about to probably spend tens of thousands of dollars on a cosmetic surgery?

If I were like the majority of people in our culture, I’d use his story as a perfect chance to shame him around his privilege. To bash him over the head with my cancer story, also reminding him that he’d never responded to my voice message where I’d told him about it. It was an opportunity for me to diminish his struggle by comparing it to mine.

I could also invalidate his experience in another way. Looking at his body in a few shirtless pictures he had on Instagram, I didn’t see any problem in the area where he was going to have this surgery. In my perception, it already looked perfect. So I could tell him, “José, you’re obsessing too much about this. You look awesome. And yes, you indeed look much younger than your age. There’s no need to spend money on this and undergo surgical risks.”

But instead, I just listened and held space for him. And when he finished sharing, I gave a response normalizing his experience. This is how developed my empathy skills had become by that moment – I could disconnect from my own circumstances and my own trauma, horrible as they were, to be fully present to another person’s experience. To the experience of someone who, as I believed at this point, was my friend. Someone who shared it with me because I was his friend.

Because, if you’re a mentally normal person with healthy boundaries, would you share something like this with someone unless you trust them and see them as a friend?

He appeared very thankful. He made me feel like my response was actually different from how other people reacted. He then went on to say that he’d also confided this to another close friend who would drive him to the surgery. Thankfully, it could all be done on an outpatient basis.

After this conversation, I felt like my trust for him increased. Like, this person dared to share his vulnerable experience with me. Could I do the same? Not now, when he was amidst his own vulnerability, but when he hopefully recovered from the surgery? The answer was a resolute yes. I no longer questioned if our connection was real.

Because I felt I was concerned about him. I wasn’t concerned about what he could do for me, but now I was concerned about him as a person. I worried if the surgery would go without complications. I worried if he’d be satisfied with the visual result. I worried about how his wound was going to heal.

On the day of his surgery, one hour before it was scheduled, I prayed for him. At that late hour, I was still at work and I sent him my selfie wearing a scrub and surgical cap with supportive words coming from my heart. I manifested my presence in his situation and appreciated that he allowed me to be present. That meant a lot to me.

“You’re an angel, Jorge,” he responded in a while. “I haven’t met anyone like you before. You have no idea how I appreciate your friendship.”

The next morning, I saw a text from him letting me know the surgery went well. I felt calmed, even though now I found myself worrying about his wound and how soon it was going to heal. Literally, I experienced his surgery exactly as I’d experienced my own hair transplant four years before. For me as someone who’d systematically studied empathy for years before, now it was the time to see what it looks like in practice. And here I was, connecting to my friend’s experience as if it were my own.

A few days later, we had another FaceTime. He looked joyous and lively, as always. First off, I asked how he was feeling and whether the wound was hurting. As someone who’d been a physician in major surgeries department for five years, I knew how different the healing process could be, and how it had to be closely monitored, especially in outpatients.

He said it was okay, and I asked when his wound was planned for revision and suture removal.

“The surgeon said there’s no need for revision, and the sutures will be absorbed within a week,” he explained. “I’ll just have to wear a dressing for another five days, then it’ll be over.”

“Good for you,” I said. Honestly, as I’d never worked in cosmetic surgery, I wasn’t familiar with the types of sutures and dressings being used – especially in the state-of-the-art American healthcare.

“I feel like the dressing itself causes me more discomfort than the wound,” he shared. “It’s so big and clumsy. But you know what? This discomfort got me thinking about physical pain, and how blessed I am to be generally healthy and only feel it for a few days after the surgery.”

Now, this was a crucial moment. For the last three years, I’d been thinking a lot about physical pain and its impact on our emotional well-being and productivity. For these three years, I’d been suffering from almost constant upper-back pain, following the shoulder injury I’d gotten at my previous job after being forced to inadequate physical labor. In Russia, I’d had no access to adequate healthcare, and common remedies like home-based yoga, stretching exercises, and tennis ball massage had almost no effect. The degree of pain varied over the days, ranging from mild to severe, where every breath felt like there was a knife moving between my spine and my left shoulder blade. And yes, amidst my overall traumatic life circumstances, this physical pain drowned me down even further emotionally. It heavily reduced my productivity – because it got worse while sitting, including sitting in front of the computer, no matter the kind of posture, chairs, and armrests I used (over three years, I tried everything available, trust me). It made driving a nightmare – because, unlike in a subway car, in an automobile, you cannot stand, and when there’s no subway in your neighborhood, you have to drive in traffic jams every day. If I lived in the West, as a healthcare worker myself, I would hardly find myself in a situation of being stricken with such a benign health issue and no opportunity to get it effectively treated. But in Russia, I was. Years of my youth were being lost to trauma, and recently, to this physical pain.

And it wasn't a three-day-long pain resulting from a cosmetic surgery. It was a three-years-long pain resulting from the injury I'd gotten as a result of being exploited in my workplace. This wasn't by any means normal.

So right now, when he brought up this topic of physical pain, it was an opportunity for me to open up about mine and the story behind it. As any vulnerable act, I knew it implied risk and emotional exposure. It implied a bid for empathy and connection. But the fact was, he’d just gotten vulnerable with me about his surgery. We were friends, as he’d told me many times. So it was appropriate to reciprocate his trust and share my experience with him.

“Well, that’s really hard.” I said, “I hadn’t told you before that I’d been living with chronic physical pain for the last three years.”

“Oh really?” he asked, with a clear look of concern on his face.

So I started telling him how this pain felt, where it came from, why I couldn’t get treatment for it…

Ha-ha-ha. No, I didn’t get to tell him any of that. His look of genuine concern faded after ten seconds of listening to my story. Then, it got replaced by a smirk, covered by an expression of politeness. He clearly wasn’t there. He wasn’t listening or paying attention. He was disengaged. My experience clearly made him uncomfortable. And he wouldn’t tolerate the discomfort. He was an upper-middle-class Hollywood man. Connection with me wasn’t worth it.

So after a minute of me talking, he just interrupted me and steered the conversation in a different direction – putting the focus back on himself. He started telling me how the wound dressing, visible through the clothes, limited his social activities – he had to bullshit the majority of his friends that he’d gotten an injury while skiing. For a moment, critical awareness crept up on me: were those people his real friends? Or were his relationships so shallow that there was no space for truth in them? Did that shallowness tell more about him, or about those people, or about Hollywood as a culture?

Well, before I could think about it, he said:

“And because of this, I had to miss this important gala event with XXX that I’d planned to attend. I just couldn’t afford to let him see me with this dressing – it’s so not sexy. Did I tell you I was dating him in the past?”

XXX – another person whose name I’m not gonna reveal – was an internationally famous A-list celebrity. Yes, a pop musician with many Grammies, Billboard hits, and platinum albums behind his belt who’d come out a decade before, after making a phenomenally successful career.

“No, you never told me you’d been dating him,” I said calmly. I saw his complacent smirk, but I wasn’t buying into it. Dating a celebrity is not an achievement. It’s a function of having access to certain social circles through privilege. There’s nothing in it to be proud of.

Well, José obviously believed otherwise. With an air of grandiosity, he eloquently told me that he’d known this celebrity through work for a long time, and three years ago, he’d started dating him. He said he’d had big expectations of “taking his life and business to the next level” through this relationship, which could end up in a marriage, but things didn’t work out. Because XXX, he said, wasn’t committed enough and approached José like “Let’s have sex, but don’t have hopes.” And, this was a dealbreaker, because José, as he said, knew about himself that he would inevitably develop an emotional bond with anyone he’d been dating. So, he emphasized, he basically rejected XXX and let go of all the big expectations he attached to this relationship. He didn’t fail to mention that this celebrity’s now-husband looks a lot like him, and that now he and XXX are still friends and collaborate on many projects.

After he finished, with the same smirk on his face, I didn’t know how to respond. I felt disgusted, but I couldn’t name my emotion at the moment. In hindsight, I see it clearly – I don’t know if I was more disgusted by José’s regret about not looking sexy in front of an ex already married to another person (which is manipulative and scarcity-based), or by the approach “Let’s have sex; don’t have hopes” that he claimed XXX had in their relationship.

“Wow, that’s an interesting story,” I said. “I hope there’s the right person down the road for you.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” he said with the same smirk, “I’m fine being single.”

No, he wasn’t fine being single. People who are fine being single don’t spend thousands of dollars on cosmetic surgeries. He just wore this complacency as an armor. But why did he tell me that story in the first place?

In retrospect, it’s clear. He was communicating the following messages: A) he was so extraordinary that he got an A-list celebrity going on dates with him; B) unlike the celebrity, who was shallow and probably promiscuous, he was looking for a profound and committed relationship; C) he’s so good at relationships that even after rejecting that celebrity, he still managed to continue working and being with him. D) he still cares a lot about “looking sexy” in front of the celebrity, and showing up with a wound dressing wasn’t an option.

So here’s how our relationship dynamics emerged in the conversation: what I was experiencing amidst my disadvantaged life circumstances in a third-world country just wasn’t important to talk about. Now, what was important was his glorious Hollywood existence: how he’d been dating an A-list celebrity and going about his cosmetic surgery. His capacity for empathy, his tolerance for discomfort, and his attention span for another person’s experience sucked.

Isn’t that a textbook situation with a narcissist?

SIGNS FROM ABOVE

I made this mistake a lot throughout my life – I didn’t believe people the first time they showed me who they were. Especially when they were people who pretended to be my friends or allies. Who made clear statements about our shared values and portrayed themselves as trustworthy. Who professed the importance they attached to their relationship with me. And, especially, when they were people who, through their privilege, had power and access I could never get from my place of disadvantage – and still sorely needed.

Here’s one clear thing about power that left me feeling small and trapped after his A-list celebrity story. I didn’t care about their upper-middle-class Hollywood gay shit, like promiscuity and shallowness. However, I did care for the stated fact that he and XXX were still friends and collaborating.

Because in my story, XXX was also a special person. Mind you, XXX wasn’t someone I’d dated or ever wanted to date. But he was someone who used to be a huge role model for me growing up – as an artist, activist, and philanthropist. He was that Hispanic singer-songwriter whose songs for the first time let me feel what true belonging was like, whose stories had healed me and given me hope, and whose memoir and coming out story informed a big source of inspiration for the plot of my book back in 2012. In the beginning of this series, I told y’all that my initial networking efforts revolved around finding a way to contact that artist. No, unlike José, I had no intention of “taking my life to the next level” by marrying him or getting money or celebrity from him. My intention was to have a meaningful conversation with him about the social issues my book addressed – social issues he also publicly championed – and the difference my work could bring to that table. I didn’t have any expectations nor did I need any guarantees. However, if my work resonated with him, this artist had plenty of connections and resources in the industry to help me put my book on the appropriate platform – the platform where it could be actually successful. And by successful, I don’t mean generating millions of dollars in sales. By successful, I mean getting the right kind and amount of exposure so this story could serve the people it had the power to serve.

But with this artist living in his A-list celebrity privilege bubble, there was no way I could have this conversation with him. As it became obvious over the years, I needed someone who had privilege and access to him in order to represent me.

And José, who did representing artistic talent for years, now made it clear he had immediate access to that person.

Guess how it made me feel.

Of course, I felt so exceptionally lucky. It was like, after so many doors shut in my face by other people, destiny again led me to that person whose work had informed a huge part of my artistic vision growing up and whose story stood at the roots of my book as my biggest creative project.

And José was someone who could represent me to him and put us in contact.

Yes, I knew I deserved that chance. I knew my work and vision and the kind of impact I could make as an artist, if helped to get out of oppression, were big enough and worth his attention. No matter how many previous people made me feel like a piece of shit from a third-world country, whose work or story by definition couldn’t matter nearly as much as the hot bodies and privilege of those who surrounded that celebrity, the truth inside of my heart could not be silenced. And the truth was, while talent is universal, opportunity is not. From that artist’s memoir, it looked like he had no problem connecting with underprivileged people. Now, even more than three years before, I had confidence and evidence to back up my work and the difference it could make in the world.

That celebrity could actually be a shallow asshole José portrayed him to be, and then he wouldn’t be interested in a work like mine. But José, as it turned out, knew many other people who could be my potential producers/collaborators. Stereotypical as it sounds, he was a Hollywood insider. And although I wasn’t looking for big fame or big money, I was looking for my work’s chance to be brought into life. He had the kind of access to make it reality. He had the skills to represent artists. And, following how he’d treated me over previous months, I believed we had a friendship. He’d given me enough reasons to believe so.

I stuck to that belief now, even though in this conversation he clearly denied me empathy and dismissed my experience as irrelevant – a complete opposite to my response to him sharing his cosmetic surgery situation. But don’t we all screw up these things every once in a while? Of course, inequal power dynamics made me think that I had to be generous, non-judgmental, and give him the benefit of the doubt.

So I decided that I would be more open about my life experience in our next conversations to come. First, because he’d framed our relationship as a friendship. And it now occurred to me that most of the time we were talking either about abstract topics or about his life. Yes, I didn’t have anything fun and exciting to share about mine, but in a friendship, does sharing always have to be fun and exciting? If we’re friends, he should be just as interested to learn about my life as I am interested to learn about his. And second, he had to know more about my life and my story because they’re inextricably connected with my artistic work – the work I eventually wanted him to represent. Because whatever negotiation skills and access he had, how could he effectively represent any artist if he didn’t understand their vision, their background, their mission, and their values?

Look, I wasn’t going to get vulnerable on the second day of knowing him. I was going to get vulnerable after months of communication, clear statements of friendship from his part, and other signals encouraging me to trust him. I was going to get vulnerable after he’d gotten vulnerable first and appreciated how I’d treated his vulnerability.

Was there anything wrong about it?

Well, no. Except for the good old lesson I’d learned by heart by then: the moment you get vulnerable – really, genuinely vulnerable, not using vulnerability as a manipulation tool – you also get to see another person’s true colors. And, after all of my experiences mentioned in previous episodes, I was afraid that his true colors were different from what he portrayed them to be.

And, most sadly, I didn’t have any other relationship on my networking horizon.

A week later, our next conversation began as if nothing were wrong. His wound healed perfectly, his body looked perfect, and he was very cheerful. Our chat went into casual topics, in a casually fluent way. However, I remembered my decision to connect on a deeper level. We were friends, weren’t we? It’s not that I would interrupt his chatter and blast him with some of my hard experiences out of nowhere. But I remember I tried to share a vulnerable story from my clinical work that was germane to the subject of our chat.

It was met with clear resistance. No, he just steered the conversation back into something trivial and fun. It was as if he said. I’m an upper-middle-class gay man from Hollywood. I do fun. I don’t do discomfort. In fact, he did little to hide that he was paying little attention – he was walking around the house, doing the dishes, taking out the garbage, brushing his teeth, rummaging through his closet… I mean, I didn’t mind any of that. But the fact he wasn’t focused on me as I was vulnerable and trying to communicate important thoughts – it was strange.

He was focused on himself, though. Instead of trying to listen to me or really understand my experience, for an umpteenth time, he started preaching to me about “surrender”.

Oh. My. Fucking. God.

Surrender was, by and large, José’s favorite word, thrown around everywhere without much thought. It was a spiritual concept meaning “stopping to fuss about the things we cannot control”.

“A while ago,” he said, “I got a deal broken that was supposed to make me sixteen thousand dollars. The client just withdrew from the deal at the last moment. And yes, I felt upset and frustrated about it. But then I just decided to surrender and trust the Universe to bring me a new deal.”

“But José, look, surrender has a limited scope,” I responded. “It’s not applicable everywhere. When we go after our big dreams in life, we have to fight, oftentimes for a long time and despite many setbacks and many naysayers, looking for new pathways and knocking on new doors, instead of just putting down our hands and waiting for the Universe to bring us what we need.”

Making my case, I went on to tell him about my deepest, dearest dream of making a career in performing arts – this truth inside of me whose voice I’d heard at the age of 12, when my hands had first touched the dilapidated piano in the public school of a poor Moscow neighborhood where I’d grown up.

Before I could finish this story, he interrupted me. Just like in the previous conversation where I made an attempt of sharing about my back pain, his attention span was very short. Instead of trying to understand and connect to my experience, he dished out a fast-food psychology response:

You know, it’s very simple. If you’re meant to be the next Britney Spears, you will. If you’re not meant, you won’t.”

He said it with this disgusting, complacent smirk on his face. And now, two years later, when I remember this moment, I wonder how I didn’t smash my fist into the screen of my old iPad when I heard him say this.

“I can’t be the next Britney Spears, first, because I have a penis, you moron,” I thought to myself, trying to smile despite my boiling anger. “I can possibly be the next Ricky Martin. But whether I will or not depends on people like you – overfed assholes standing at the gates of this industry. You decide what’s meant to be and what’s not meant to be in my career. And you fucking know this.”

Of course, he knew this. His complacent smirk communicated that knowing. Of course, as soon as I exposed my vulnerability, he quickly sniffed the power he had in our relationship.

I remember I was baffled by his response. For the first time over the months of our “friendship”, I didn’t know what to say and how to react. I wanted this FaceTime to be over as soon as possible. He hurt me. I still didn’t understand clearly if he did this purposefully, and if so, why. But it was real, and we had to talk about it. That’s not how friendship works, and I never deserved to have my vulnerability be treated like that.

A BID FOR CLARITY

So in the middle of the following week, I sent him an email clearly sharing my concerns. I told him how I felt after our recent conversations. I said I was making up a story that he wasn’t comfortable with my vulnerability. I said it was okay but he had to make it clear. Clarity of intention and boundaries is one of the most important things in relationships. I didn’t write it but I thought back to his story about dating XXX: “Let’s have sex, but don’t have hopes” may sound disgustingly shallow and promiscuous, but it’s honest and clear. It allowed José to choose whether to stay in this relationship or quit it.

So now, I wanted to get the same clarity from him. I didn’t shame or attack him. I shared how I felt and respectfully asked him to help me understand what was going on on his side.

He never replied to that email. Remarkably, reviewing our whole relationship, I can tell this was my only email he never replied to.

Because it was a request for clarity. And clarity is one of three things you never get in abusive relationships.

The next weekend, we had another FaceTime. And guess how he showed up? No, he didn’t say anything about my email. But instead of that, he again was his “normal self”. I mean, there was no complacent smirk and no air of superiority. He was again the down-to-earth, raw, smart, funny José I’d known as a long-distance friend. He was again the José chatting with me naturally and making me feel like we were equal.

This is, by far, the most fatal weapon of a narcissist — gaslighting. These people make you question your sanity by constantly changing how they treat you and how they show up. Like, one day they crush you down emotionally, and the next day they're again your best friend. Or one day they dismiss your ideas as irrelevant and the next day they tell you how brilliant the self-same are.

This pattern emerged even clearer in his further behavior, which y’all will see below. Abusers have to employ these tactics to keep their targets hooked. To undermine their target’s sense of reality. To erase their boundaries. They do it so artfully that unless you collect the evidence of their inconsistent communication – like screenshots or call recordings, you’ll be effectively manipulated into believing that their harmful behavior never happened, or at least that it wasn’t intentional (and therefore, there shouldn’t be any accountability around it).

Now, consider how this typical mechanism of abuse was enhanced in the particular situation between me and him, characterized by huge, objective disparity of power and privilege. Consider how I was feeling, believing that a friendship with someone like him was the one-in-a-million chance I could get in my disadvantaged life. Consider how desperately I stuck to the initial assumption that, after all, he was a good person who just did a couple of bad things.

I walked away from that FaceTime full of hope and soothed. It was somehow lost on me that he still ignored my straightforward question from the email. Following his gaslighting, I happily deluded myself into thinking that his neglect and insensitivity weren’t real – I’d just made it up, probably based on my previous toxic experiences.

So the next week, before another scheduled FaceTime, I texted him saying that I had to talk to him about an important thing related to my work. I intended to start telling him about my book, and mention my story piece by piece along the narrative, insofar as it was related to my book. Anyway, he became aware I had something important to talk about in the upcoming conversation.

And now guess, how the conversation turned out?

He made a clear effort to keep it fun and shallow – telling me about his glorious Hollywood life. Like making another deal, shooting another campaign, going to another party with his no less fortunate friends. A few times, when I made a communication bid to finally start talking about this important thing I wanted to share, he rapidly steered the conversation back into fun, fast, and easy. No, he wasn’t in the mood for real connection. And no matter what was important to me, why it was important, why I wanted to share it – he wasn’t having it, but in a perfectly polite, American bleached-smile manner, without saying it outright in my face.

Huge lesson: when a person professing friendship, love, loyalty etc. to you then makes you feel like there's no space for your vulnerability — in a conversation, at the dinner table, or in the relationship as a whole — it's a no-win situation.

During that conversation, it was like he made me wait for the right moment to finally switch the gears towards my matter. But guess what? He knew very well we didn’t have a big time window. After an hour of trivial chatter, he just said goodbye because he had to go on with his day.

At this stage, aware of my vulnerability that his previous friendship statements successfully created, he took over the conversation lead and framed it however he liked. He already felt he could get away with disrespecting me. He knew his privilege gave him the license and entitlement, and I would have to accept anything, anyway.

As a final note, he added that we weren’t going to have a FaceTime the next weekend because he was going to Burning Man with his friends. I was yet to research about this festival, which every year gathered America’s rich and powerful to celebrate their privilege.

How important could my life, my art, and my story be compared to his excitement about Burning Man?

BURNING MAN

In the absence of clarity, I was effectively gaslighted to still allow the possibility of meaningful connection with him. Like, didn’t he talk all those eloquent talks about us being friends? Didn’t he trust me with his cosmetic surgery story because we were friends?

I still didn’t have enough evidence to see that all of that was epic hypocrisy and manipulation.

As José and his friends went to celebrate their privilege at Burning Man, I found myself face-to-face with my reality: the traumatic circumstances of my life in Russia grew worse and worse. Now, it’d been one year since having my skin tumor diagnosed. If it was actually melanoma, which was about 60% likely, my prognosis was already poor given the treatment delay of one year. It goes without saying that there was still no way I could earn the budget to perform this affordable, non-invasive, outpatient surgery in Europe, and no opportunity to get it in Russia. My economic reality got even worse than it had been, as the clinic where I worked part-time experienced a further decline in the number of patients, and the workplace rumor had that it was about to close down soon. Given the horrible employment situation in Russian healthcare, I didn’t know if I would find another job – if only one yet shittier than this was. To make it measurable: that summer, when José was having a cosmetic surgery and went to parties in the Caribbean and Burning Man with his friends, my monthly income went below $100 a month. Food and gas expenses and other inevitable bills had to be paid, and my savings were coming to an end. In August, I had to start withdrawing money from my emergency account. No matter how poor I was, it was the account where for years I kept the little budget for a visa fee and one air ticket to Europe or America, thinking of the day I would fly there for negotiations about my book.

But despite three years of my networking efforts, as I practiced exemplary courage and integrity and showed up with my talent and my artistic commitment to make the world a better place, this day never came about.

And now, just like I had buried my expired American visa in January, I had to bury the hope to even buy an air ticket with my own money. Because otherwise, next month I wouldn’t have the money to buy food.

Speaking of money, there’s one thing totally worth mentioning. Despite the abyss of economic difference between me, a poverty-stricken guy from a third-world country, and José, an upper-middle-class man from Los Angeles, I was never jealous for his wealth – instead, many times throughout our conversations I found myself feeling like he needed my help with the money. Sounds crazy? Here’s what I mean.

I cannot tell you how often he mentioned he couldn’t get out of credit card debt. WTF? Are you bullshitting me? I thought first. Because I saw the economic standard of his life. Parties, vacations at luxury resorts many times a year, one of the most expensive Mercedes-Benz models – and with all these ongoing expenses, couldn’t he pay back the bank? Initially, I believed he just told me this to appear more relatable. But he repeated it over and over again, and then he shared that he was considering hiring a financial advisor because this “credit card thing” was stressing him out too much.

I offered him empathy, but I still didn’t see why he couldn’t figure it out. How could it be that an upper-middle-class American person, enjoying huge economic opportunity even compared to other people in his country – never mind third-world country folks like me – how could it be that he wasn’t able to get out of his credit card debt? He earned more than enough. Far more than was necessary to cover basic needs. If this “credit card thing” stressed him out as much as he claimed, couldn’t he just restructure his expenses for a couple of months? Did he have to buy/lease the most expensive AMG version of his Mercedes-Benz model, or could he save $25k buying/leasing a regular version – and close his loan as a result? Or, more radically, couldn’t he get a Toyota Prius instead of a Mercedes-Benz?

Look, I hate doing math about other people’s incomes and expenses, but one thing I know for sure. As someone growing up with adults unreliable in all aspects, financial included, I had to learn personal finance very early in my life – how to save, how to budget, how to plan ahead, etc. Living and working in a country with small economic opportunity, and earning sums risible in terms of Western standards, and almost never having discretional income, I still always had money in my savings account. No matter the comparison and consumerism prevalent in our global culture, I never spent money on things before I earned that money. Like, when most people around me freaked out about new iPhone models they got, I still managed with an old flip phone. There was no way I could take bank loans for anything, probably because in my profession I never had security. My legal salary was risible, and 90% of my income came from tips. I could never know for sure whether or not next month I was going to make a certain amount of money – so borrowing from the bank wasn’t an option. The only time I maxed out my credit card was in September 2015, when after the two-fold devaluation of Russian ruble the previous winter, RUB/USD rate started to decline even further – so I had to convert the rest of my ruble savings into dollars, and since the savings were on a deposit I couldn’t withdraw from immediately, I bought out dollars with credit card money. But I did so only because this was the rare occasion where I had security – I knew I would get my deposit back within a month, during the remaining grace period on my credit card, meaning that I wouldn’t have to pay a penny of interest rate to the bank. Basically, in all of those rare occasions in my life where I used loan money on my credit card, I wound up paying zero interest to the bank because I planned my finances ahead. I knew for sure – almost for sure – that I’d be able to pay the debt within the grace period.

It kinda blew my mind to realize that, as a person living almost my entire life in poverty, I’d never found myself “unable to get out of a credit card debt”. There was no magic here. I wasn’t better or smarter with money than anyone else. I just had the skills, learned out of necessity. And now, when I saw an upper-middle-class man from Hollywood struggle with this, it was kinda obvious that his inability to get out of credit card debt resulted from lack of those skills: reasonable spending, planning, and budgeting. That’s where, crazy as it sounds, he could actually need my help. Which, unlike his prospective financial advisor, I was willing to give him for free.

So technically, me and José both struggled with money. But while my struggle resulted from lack of economic opportunity in my country, his struggle had to do with his overspending. While my struggle kept me in food insecurity and lack of healthcare access, he, despite his struggle, dined at restaurants and had cosmetic surgeries. Therefore, the emotional experience underlying my struggle was fundamentally different from the one underlying his. His experience was shame over comparison-driven overspending. Mine was powerlessness amidst the disadvantage I never got to choose.

DEVALUATION

SEPTEMBER

We had our next conversation when he came back from Burning Man. Predictably, he shared what an extraordinary, incredible experience the festival had been. Interestingly, it was the first time in our relationship when after him asking me “How are you?”, I distinctly felt that he didn’t want to hear the response. He asked that out of politeness, not genuine care. Nevertheless, enjoying telling me his awesome Burning Man stories, he acted like he was entitled to my care. Like I was supposed to always be interested about his glorious, fortunate life – even when it was tainted by “the credit card thing” and by the shame over having a cosmetic surgery and not “looking sexy” in front of an A-list celebrity he’d once dated.

Somehow, in this FaceTime we again came across his favorite topic of “surrender”, and, making his case, he clearly showed his abusive, misleading interpretation of it. He said, “I know you think you’d be happy if you moved over to the U.S., but actually you’re wrong. You don’t know what would happen to you here. You could get hit by a bus on your second day of being in this country…”

I felt shocked, and insulted, and diminished. Because his words flagrantly violated the truth. First, I’d never believed moving to the U.S. would make me happy. I’d never said I wanted to move to the U.S. in the first place, because I didn’t want that. It was an arrogant assumption of a successful Hollywood man – that someone struggling a third-world country could only want to immigrate to America. He never bothered to be curious and learn the truth, which was bigger and more complex than what could fit in his narcissistic mind: I was indeed looking for the opportunity to leave Russia, but the place I wanted to move to was Spain. Because Spain was my place of true belonging. As to the U.S., I knew I might have to move there for a while, to study and work in my artistic profession, but it definitely wasn’t where I wanted to settle. And sure as hell, I didn’t think that moving anywhere in and of itself could make me happy. It was a blatant trivialization of my experience.

What was real, nevertheless, is that if I lived in America, as a doctor with eight years of clinical experience and the highest scoring diploma from one of the country’s top medical schools, I definitely wouldn’t find myself in poverty. I definitely wouldn’t live in food insecurity and without access to healthcare. I could still suffer from my creativity being unclaimed and unused, from my true calling being not honored, but I definitely wouldn’t undergo multilateral trauma.

And as to the bus – I could get hit by it in Russia, in Spain, in America, or in China, for that matter, as well. What did it have to do with moving, or not moving, to another country?

Well, because the core message of his bullshit was clear – I had to “surrender” (i.e. give up) to the realities of my life in Russia. It’s not the story I’m making up, because as you’ll see from the following events, that’s exactly what he meant.

Which prompts the following question – if he was trying to convince me that life in the U.S. wasn’t really worth moving towards, then why, on his podcast, did he feature and honor his Venezuelan doctor friend who’d recently immigrated? Why didn’t he himself consider leaving his nice house, his brand new Mercedes-Benz, his $20k deals, and his glorious Hollywood life and just moving back to Venezuela, his native country that was now falling apart under oppression, corruption, and dictatorship?

The thing is, José didn’t left leave Venezuela in the same way, in the same context, and under the same circumstances as those in which modern-day Venezuelans flee from the country. José had left almost thirty years ago, at the age of 12, because his grandparents had already lived in Miami. He’d moved at the expense of his family – by virtue of privilege, essentially. Then, he went to middle school and high school and college and Florida. And then, after graduating, he moved to New York where he started working as a photographer agent in the fashion industry. Given how burgeoning this industry was in the city, that’s where all his connections and security had sprouted before he moved to LA and started representing talent in Hollywood and producing campaigns for big brands. So in his fortunate, predominantly American life, he never had to create the opportunity for emigration through his own effort – the opportunity was already here because of his family.

Given the young age at which he left Venezuela, one might assume that he didn’t remember what a third-would-country existence looked like. That he didn’t remember the poverty and the oppression and the corruption. But as it turned out, he did. Once on his podcast, he shared that walking into grocery stores in America he still found himself recalling how those had looked in Caracas in his childhood – yes, even in those years when the economic situation in the country hadn’t been as grim as it got now. Moreover, he still had his Dad and some relatives living in the country. He knew how tough it was. And, every time he spoke about them, it looked like he empathized with their experience.

Then, the question became, why did he trivialize mine?

Why this double standard?

The answer was, because I and he were already in the second phase of narcissistic abuse: devaluating. Unlike in the first phase, where he bombed me with messages of respect, friendship, and appreciation, now he didn’t hesitate much to hurt me – exactly in the areas he knew were the most sensitive. In the areas in which he’d encouraged me to be vulnerable. He was doing it purposefully – making me feel that unlike his Venezuelan friends and relatives, whose experience he recognized and respected, I didn’t deserve recognition and respect of mine.

Remarkably, it was around the same time – in this conversation, or the next one in September, where he started to openly put down the concept of empathy. He said: “I don’t think empathy makes much sense, because we can never see the world how the other person sees it. So just acknowledging we cannot do it is enough.”

That was epic bullshit. I hadn’t researched empathy for the fun of it. I knew well how to call BS on such rhetoric. I told him that empathy doesn’t require him to see the world exactly as another person sees it – because the lenses through which we see the world, informed by aspects of identity and personal experience, are unique and they’re soldered to our faces. There’s no way I can put down my lens, pick up the other person’s lens and see their experience through their lens. But real empathy doesn’t even require that. Instead, it requires that we recognize and unconditionally accept the emotions underpinning another person’s experience – even when the particulars, the circumstances, and the perspective of that experience are not relatable to us. Then, empathy requires that we connect with the same emotion within ourselves and communicate it back to another person. That’s how we learn to be here for them in a way that’s meaningful, helpful, and healing.

But, no, he wasn’t buying it. He still stood that empathy wasn’t possible, and not even worth trying. He was openly cynical and skeptical about it.

His rhetoric could be summarized and decoded to this: “I’m not willing to try to understand other people’s experiences when those aren’t fun, fast, and easy. Connecting to their emotions is uncomfortable, and I’m not doing discomfort.”

Make no mistake: this person putting down empathy in front of me now hosted a podcast about spirituality. He was a die-hard fan of Oprah. And yes, he was basically trying to tell me that empathy was bullshit. How cute is that? And why wouldn’t he say this on the mic or in front of the camera?

Moreover, when I shared what I’d learned about barriers to empathy from the evidence-based research of Brené Brown – the world-renowned research informed by hundreds of thousands of real-life interviews, processed with the grounded theory methodology – he responded, “Well, you know, it’s just a theory.”

He said that with the same complacent smirk on his face, which obviously communicated: “This information makes me uncomfortable, so I won’t recognize its importance.”

Because, in his picture of the world, comfort was invariably favored over truth. And just because he didn't say it out loud, it didn't change that these priorities were observable and measurable in his behavior.

Even more interesting, just a few months ago, when I shared with him the exact same ideas and findings about empathy from my research, he responded by saying “how brilliant I was” and that I had to start my own podcast.

Isn’t that another gaslighting move, so often used by narcissists in the devaluating phase?

OCTOBER

In the beginning of October, he took denials of empathy, and the process of devaluating me, to the next level.

His birthday was on the first week of the month, and mine was nine days later. We were both Libras, and I remember him saying that this was why “we were such good friends”. I was no longer sure about that in the light of how he was treating me, but anyway, he talked a lot about how excited he felt about his birthday. How his past year had been full of blessings, and how he saw more exciting things in the year to come – like doing new projects, doing more comedy stand-ups, and taking his podcast to some TV production company. Yes, another time he didn’t hesitate to wave his privilege in my face.

Given how close our birthdays were on the calendar, it was logical that after sharing how he felt about his birthday, he would ask me how I felt about mine. Because normal, healthy friendship is a reciprocal relationship. It cannot revolve around the life experience of one person and dismiss that of the other.

But no, he didn’t ask me. And this was the moment where I stepped in, trying to make our conversational and relational dynamic more equal.

No, I didn’t shame or confront him about why he wasn’t interested in my birthday experience. I still assumed he did care, because just in the beginning of that conversation he mentioned we were good friends. So I just started sharing with him how I felt. Because in a friendship, there should be space for this.

I told him that I was feeling grief. That for the last four years, every time my birthday approached in mid-October, I didn’t feel like celebrating anything. Because every year, it was the calendar mark at which I understood that I got one year older, but despite my continuing, committed efforts, my life hadn’t moved an inch closer to my most important goals. That I still lived in poverty and food insecurity in a third-world country. That my creativity still lay unused and unclaimed and unable to serve the world. That I still didn’t get to begin the career where my biggest gifts could be actualized – and the older I got, the smaller the chance at succeeding in this career became. That despite showing up in the arena, despite being brave with my life, despite working my ass off to make my dreams happen, despite rising strong after people abused me and shut doors in my face – despite living and working from integrity and with full-time, dead-serious commitment to creativity, I still stayed trapped in the same never-ending misery and multilateral trauma. I felt like time was slipping away like sand through my fingers. I felt like I was lagging behind more and more, and although there was no way I was going to leave the race, with every year I saw increasingly that the magnitude of talent and the surplus of effort could not outweigh my deficit of privilege. This year, I added, I was in even deeper grief, because on top of my chronic back pain and other health issues, in the absence of access to adequate healthcare I had this probably malignant skin tumor, and it’d been more than one year since it was diagnosed, so I wasn’t sure I would make it to my next birthday…

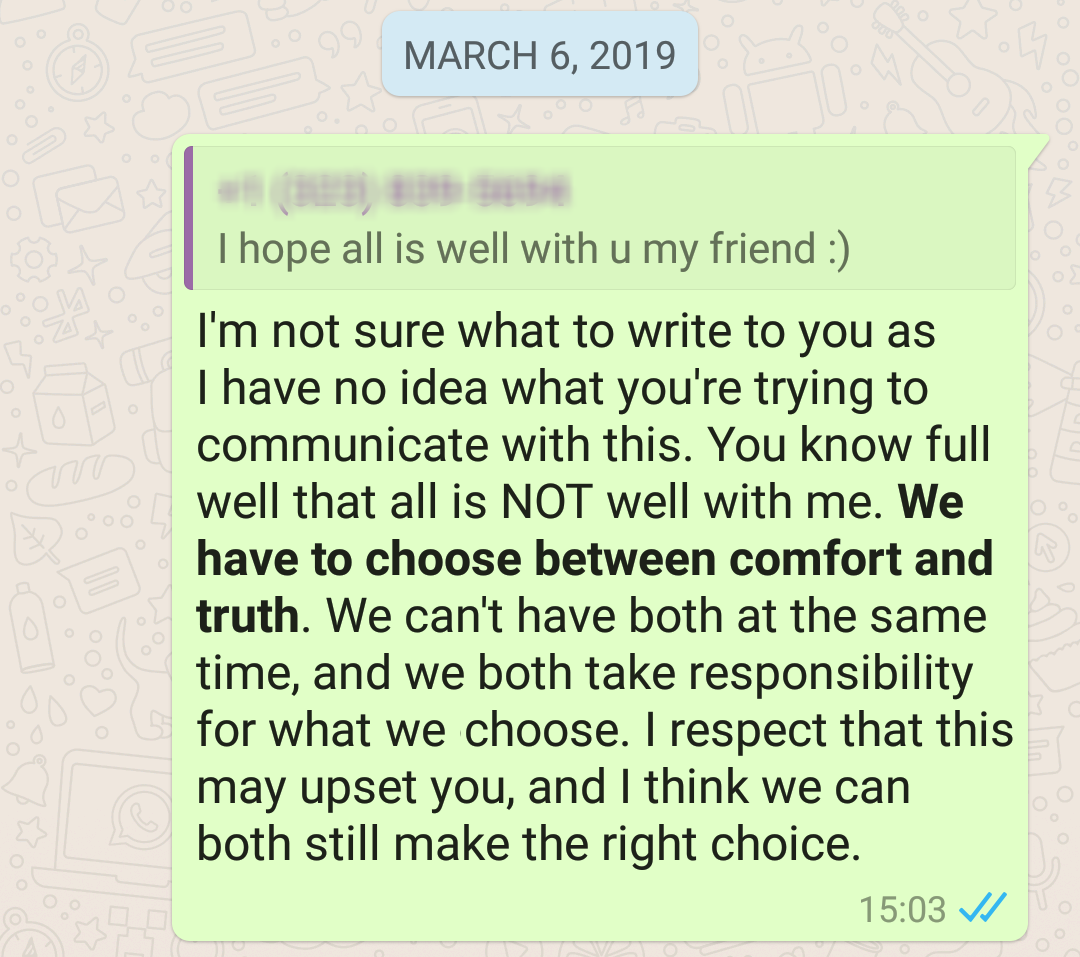

“Wait, wait, wait,” he interrupted me. “Do you have a tumor?”